Of Aerials and Virtue

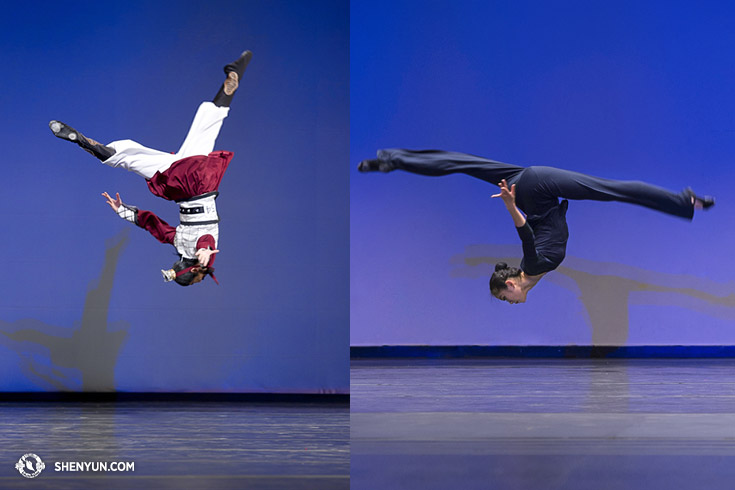

Of the many classical Chinese dance techniques, some of the most challenging are the ones that soar above your head. In Shen Yun performances, you’ll often see our dancers tumbling in mid-air. These techniques act as finishing touches, just like pepper sprinkled over scrambled eggs, or stars twinkling around a full moon—they’re not the main characters, but they help push a dance up to its pinnacle.

Sometimes, the dancer will perform a whole sequence of xiǎo fān (小翻), or back handsprings; other times, it’s just one lā lā tí (拉拉提), a.k.a. a layout-stepout in gymnastics. These movements may last only a few seconds, but as the saying goes, “One minute onstage equals 10 years of hard work offstage.” When learning these techniques, we count practice repetitions in big numbers; after several hundred repetitions you finally become a beginner.

Every step I take down this path of mastering the art of tumbling has changed me both physically and mentally. When I first started learning, all I could think of were various requirements—“swing your arms”; “look up”; “keep those legs straight!” That’s entry level. It’s very basic and boring. But you can’t do without it.

Once you’ve laid a solid foundation, next on the training agenda is gaining better control of your body. You have to practice until you can coordinate all your muscles—including tiny ones you didn’t even know existed—as well as control your speed, direction, and spacing. Only then can you graduate to the next level.

At this next level, you don’t need to focus as much on the surface skills; rather, it’s more about abstract ideas.

For example, before each flip, a dancer is required to have a certain stance, like a dragon in the clouds, waiting to unleash his might, or a tiger getting ready to pounce. You can look at someone about to perform a flip—even before he raises his arms, just by glancing at his stance, you can tell how good his flip will be.

And it’s not just the physical posture—your mental stance is critical, too. You need to surround yourself with a big aura. That’s why some dancers don’t like others getting too close when they’re about to flip—it’s not that they’re afraid of hitting them or getting tripped, but that they’d rather not have any intruders in their space. On the first step of your running prep, you must have the unstoppable power of water gushing out from a dam.

A dancer’s mental state really is the most important thing. And to achieve the best mental state requires a cultivation of one’s heart. We believe that a dancer’s mindset and attitude change according to his moral character. It’s like the old Chinese expression—“you need both virtue and skill” (德術兼備, dé shù jiān bèi).

Classical Chinese dance, which integrates so many technical components, is even more an embodiment of moral values. Just as in Chinese kung fu there is wǔ dé (武德), “the martial artist’s moral code,” so is there wǔ dé (舞德), the “dancer’s moral code,” in Chinese dance (more about the relationship between Chinese dance and martial arts).

If a dancer’s mind isn’t in the right place, his performance is merely a product of technical skill and not a work of art. If we believe that the role of art in society is to promote integrity and goodness, even spiritual elevation and inner peace—then a dancer’s inner world becomes very important.

Ancient Chinese believed that moral virtue links Heaven, Earth, and humankind. Traditional art, like classical Chinese dance, is rooted in this concept of harmony. Like a perfectly executed flip, these art forms can uplift us, bringing us a little closer to heaven.

Zack Chan

Dancer

Dancer

May 2, 2016